Exam Grading

This section will outline the specific protocols pertaining to grading exams on Gradescope, but the tips will be useful for written assignment grading as well.

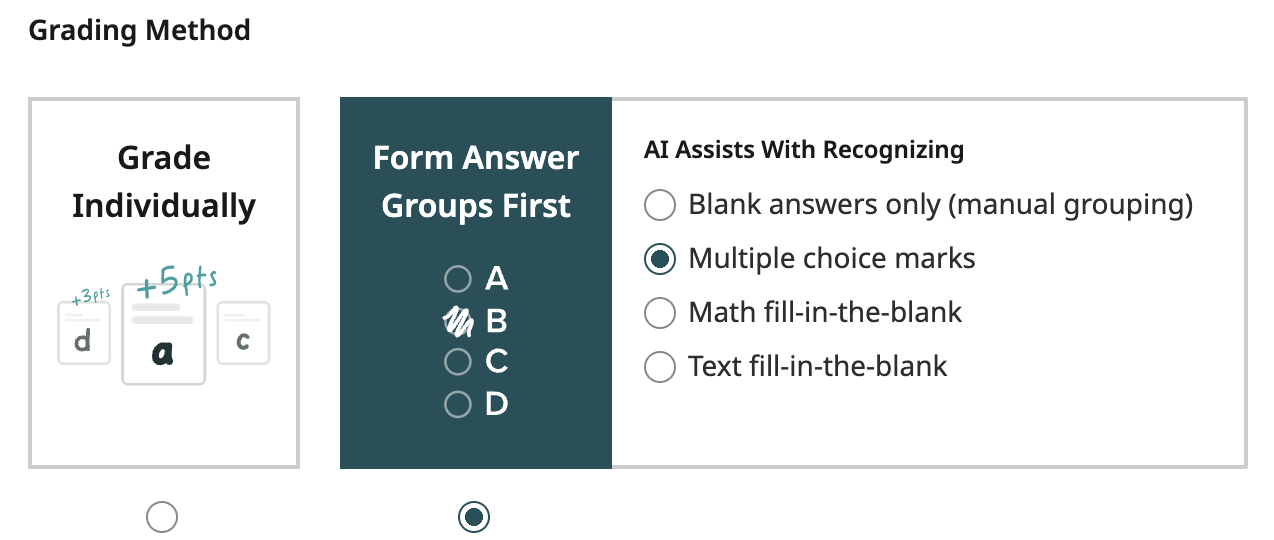

Answer Groups

When grading a question, you’re given the option of grading individually, or specific answer groups: blank answers, multiple choice, text, or math. Multiple choice is self-explanatory.

Text/math: When doing text or math, the algorithm will evaluate all text within the box you’ve selected for the answer outline, which is why restricting the outline box to the answer box will help eliminate erroneous groupings that include scratch work.

If you intend to evaluate an answer fully taking the work they show into account, it is likely fine to include both the answer box and the scratch work box and just do blank answer grouping.

Blank answer grouping: For all questions requiring explanations of one or more sentences, you should almost always be grouping by blank answers, not grading individually. Here is one framework that has worked well historically across several classes:

- Create three default answer groups: Blank, Fully incorrect, Fully correct. For answers you’re 100% sure deserve no points or full points respectively, add them to these answer groups.

- For every response you’re unsure of, create a new answer group describing what this response did. Add all future responses matching this to this answer group.

- You will end up with between 4-10 answer groups, depending on the question. Now just create a rubric that captures these answer groups and grade!

Because grouping responses into answer groups takes the vast majority of the time, this method ends up being just as fast as grading individual responses 1 by 1, if not faster. In addition to this, there are a few notable benefits of grading this way over grading individual responses:

- It is very easy to go back and update the rubric, because assigning a new grade to every answer group is much faster than going through every individual response.

- It keeps the responses very well-structured. Even if you don’t quite know how to assign points to a question yet, you can complete 98% of the grading overhead simply by category grouping.

- The answer groups you create serve as a log of the responses your students provide, as well as how many students wrote each response. Such is useful data for the future.

Creating Rubrics

Hopefully during the exam writing phase, the exam writers wrote the question with some idea of how they wished to grade the question. However, even after you have scanned the exams, there are some things to consider:

- Look at a few submissions (e.g. 10-20 of them) to see how students actually answered the questions. This can give you more ideas for alternate solutions or how to award partial credit. It can also provide a signal of whether the question was too easy or too hard (and to adjust grading accordingly).

- Be aware of any clarifications that were announced during the exam that may affect grading.

- Be aware that there may be multiple ways to solve a particular problem.

- Avoid double jeopardy wherever possible, e.g. don’t penalize students twice for the same mistake if a problem builds off a previous one.

- Unless that is the learning objective for the exam, avoid penalizing small “formatting” mistakes such as minor syntax or spelling errors.

- If you do decide to penalize students for errors like these, make it clear in your rubric what you penalized so that graders can apply the rubric consistently. For example, rather than

-0.5 Minor error, the rubric item could say-0.5 Minor syntax error.

- If you do decide to penalize students for errors like these, make it clear in your rubric what you penalized so that graders can apply the rubric consistently. For example, rather than

- Make your rubric items as specific as possible. This can make grading more efficient (staff don’t need to refer back to an answer key) and make point adjustments much easier. For example, if halfway through grading you realize that your MCQ had 2 correct answer options instead of 1, you can quickly change the point value for the previously incorrect option and that will automatically affect all students with that rubric item applied.

- Have different rubric items for

+0 Incorrectand+0 Blank. You may wish to be even more granular and record every single incorrect answer option as a separate rubric item (this is useful for changing point values and to see if there are patterns of misunderstanding amongst students). - For MCQ or multi-select questions, have a rubric item for each option, even if it’s incorrect.

- Gradescope can automatically calculate useful statistics such as what percentage of students have a rubric item applied, which can be useful for pedagogy.

- Have different rubric items for

- Build partial credit into the rubric. For example, here is a rubric you might have for a short answer coding question in Python that awards partial credit for an off-by-one list indexing error:

+1 Correct: lst[i + 1]+0.5 Partial: lst[i]+0 Incorrect+0 Blank

- Be aware that Gradescope autograding feature for online assignments is very particular. For example, if you have a short answer question box, it will only mark answers correct if the string is an exact match. In the assignment settings, you can strip leading/trailing whitespace and enable case insensitive matching for short answer questions. Otherwise, you may wish to manually grade all short and long answer text boxes. Similarly, for multi-select questions, Gradescope will autograde those using the all or nothing grading scheme; if you wish to use a different scheme you will need to manually grade those questions.

- If you update the rubric while grading, make sure to go back and check previously graded submissions to see if the rubric changes apply to those submissions.

- When grading exams with multiple versions on Gradescope, you can import the rubric from the first version of the exam.

Multi-Select Question Grading Schemes

| Scheme | Description | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| All or nothing | Students must select exactly the correct subset of options to get full credit on the question. Otherwise, they receive 0 points on the question. | Students must be very precise in answering, which discourages frivolous guessing. | There is no partial credit, so even if students demonstrate some understanding they won’t get rewarded for it. |

| Additive partial credit | Let n be the total points possible for the question and m be the total number of options (both correct and incorrect). In this grading scheme, each option has a rubric item of +n/m points for correctly selecting that option or correctly NOT selecting that option. |

This scheme does not punish students for incorrect selection or lack of selection. | This scheme rewards students who have a strategy of selecting all answer options if a majority of the options should be selected. Conversely, it rewards students who have a strategy of selecting nothing if a majority of the options should NOT be selected. |

| Additive and subtractive partial credit | Let n be the total points possible for the question and k be the total number of correct options. In this grading scheme, each correct option the student selects awards them +n/k points and each incorrect option they selected awards them -n/k points. Additionally, to prevent negative total points or more points than the question is worth, have a point floor of 0 and a point ceiling of n. |

This scheme discourages frivolous guessing while still allowing students to get partial credit. It also ensures that a student who selects all options or selects none of the options gets 0 points. | It can be frustrating for students to receive 0 points in a question even if they selected some correct options. For example, this can happen if they selected an equal number of correct and incorrect options. |

Assigning points

A quick note on point assignment. The purpose of an exam is to test a student’s understanding on certain topics. The most objective way we currently have is assigning points on questions for student answers. On one hand, the most important part of exam grading is having a consistent rubric that is applied equitably for every student. In addition to this though, it matters too that the answers that are neither fully correct nor fully incorrect are assigned points roughly proportionate to how correct they are.

For instance, suppose you give students a question, “Explain how an inode-based file system works.” A fully correct response might be one that briefly describes direct pointers and indirect pointers, and that they make extending a file very natural (providing reasons why). We’ll go through two example responses and explain how grading it might work:

- Explains what direct/indirect pointers are, that they substantially increase max file size.

- Explains what direct/indirect pointers are, that having tiers of pointers balances faster access to small files and support for bigger files simultaneously.

Let’s suppose 2. is fully correct, and 1. is partially correct. In deciding how many points to assign to each response, it’s important to think: in the context of this class, how much more does a student have to understand about inodes to understand what 2. is saying versus what 1. is saying? In other words, roughly what percentage of the total knowledge does 1. capture?

These ideas apply to both free response and numerical answers. Suppose you are deciding how to assign partial credit to a response which is off by 1, or off by a factor of 2. The same questions arise: what percentage of complete understanding does the student have to grasp to arrive at this almost correct answer?

These questions will be left as a thought experiment for the reader, who is encouraged to think about their own exams and how framing exam grading in this way might influence rubrics.

Resources

- Relevant Gradescope docs